The Bevica Scholarship Programme online learning modules consists of an Introduction Package and three online self-study modules. These modules serve as a basic introduction to the core objectives of this year’s Scholarship call to:

The three modules provide a mix of book chapters, digital talks and lectures, scientific papers, and podcasts on the general themes of: Universal Design, Being Human and Leave No One Behind. Each module consists of 5-6 mandatory references for you to study at your own pace during Ideation. Supplementary readings are listed for each module. These are not mandatory but meant as inspirations for you to pick and choose from.

Full catalogue of references can be retrieved by clicking the “All Reading” button below. The modules support participants in their ambition to innovate and demonstrate inclusive approaches to human beings, and to explore universal design as a value-based design principle which supports the pledge to Leave No One Behind in a future sustainable society. They offer different disciplinary and academic understandings of the three core themes and serve as a basic outset for individual investigations. They are by no means to be understood as exhaustive.

You are encouraged to expand your investigations beyond the core modules, and to seek advice and inspiration from the peers and experts you meet during Ideation.

This Introduction Package serves as a basic introduction to the core objectives of this year’s Bevica Scholarship call: Universal Design, Being Human and Leave No One Behind.

The Package consists of 5 key references: two texts and

three videos.

Before we meet at the Ideation Workshop on 1 February, you are expected

to have studied the references of the Introduction Package.

Your preparation will ensure a common knowledge base for all

participants and as a basic framework for understanding, discussion and

preliminary ideation of your individual project proposals.

Universal design is first and foremost a concept that recognises that human beings all live with impaired and changing abilities – it is a universal condition of being human. In this understanding of universal design, the concept holds the potential to transform and challenge our common understanding of what average and ideal means with regard to human bodies, and what it means to be human.

Universal design was coined by American architect Ron Mace in the 1980s. Mace taught at the School of Architecture at North Carolina State University (NCSU), and he was a wheelchair user himself. In his practice, Mace found that solutions defined as “accessible” or “barrier-free” often ended up stigmatising and exposing the user, even though the intention was the opposite.

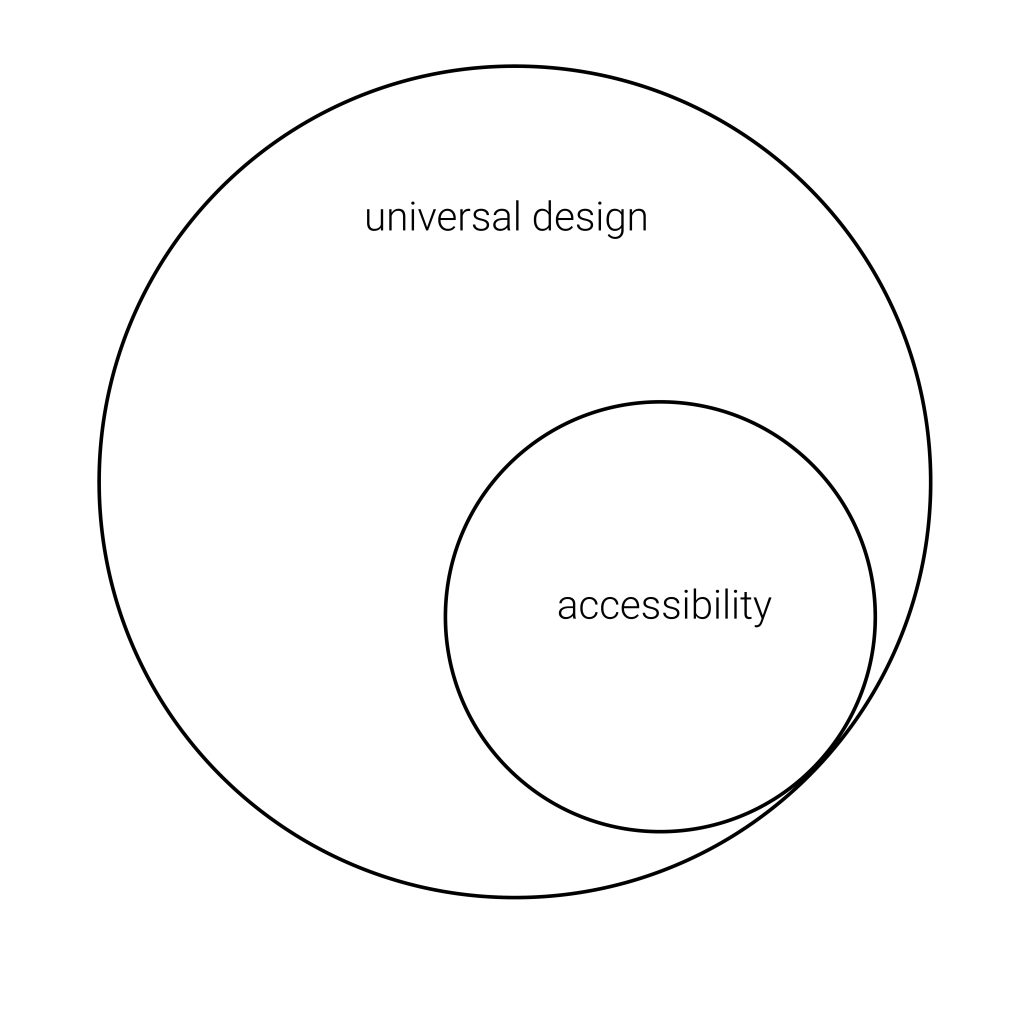

Illustration: Camilla Ryhl

By focusing on the particular needs of a specific user group, the available solutions were not integrated into the design process; nor did they become part of the main solution or concept. Accessible design solutions were practiced as “add-ons”, and although the intention was the opposite, such solutions were often experienced as exposing rather than including.

As an alternative, universal design represents a design principle that addresses human diversity and focuses on solutions that meet people’s various needs.

Universal design was originally developed as a design and architectural concept. However, over time, the concept has branched out, so that now it is applied in many professional and interdisciplinary contexts, as well as in larger international conventions and regulations. Despite different approaches and interpretations of the concept of universal design, the essence is to create inclusive societies accommodating all of human diversity.

In 2006, universal design was written into the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) as a general obligation, which meant that the concept was introduced in a Danish context. All countries joining the convention have thus committed themselves to integrate and develop universal design in research, education, and politics. The CRPD uses Mace’s original definition, although with the addition of programmes and services:

[Universal design is] ‘the design of products, environments, programmes, and services to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design’. (UN CRPD, article 2, 2006)

By expanding the scope to include programmes and services, universal design is no longer only an architecture and design principle but is now a multi-disciplinary concept to be implemented and practiced in all aspects of the lives we live. And as such, universal design can serve as a multi-disciplinary lever for the overarching commitment to Leave No One Behind in the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Universal design offers a value-based framework for designing, planning and developing programmes, services and solutions which do not divide people into groups with and without impairment. Instead, universal design acknowledges from the start that people are different and by embracing human diversity as a pre-requisite for all designs, regardless of discipline, scale, or sector, it is possible to create a society that includes and embraces everyone, with all our physiological differences. This is what universal design can support, so that we ultimately gain a broader understanding of what it means to be human.

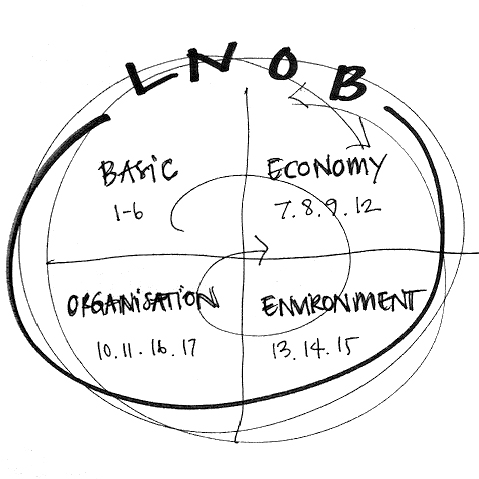

Illustration: Camilla Ryhl

In Danish society, we often categorize people as “with and without disabilities”, rather than recognising that everyone lives with different abilities and the diversity of user needs means that humans do not come in standard sizes. This understanding of being human creates a “Them and Us” which does not contribute positively to a sense of community or a society for all. Instead, the categories create a society with solutions for some and different solutions for others.

In efforts to meet more nuanced and relational understanding of disability, we point to a more faceted international view: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF 2001) formulated by the World Health Organization. In this type of classification, a person’s ability and disability is identified as a relational phenomenon, an interaction between individual bodily conditions and contextual factors.

According to the World Health Organization, ‘a person’s functioning and disability is conceived as a dynamic interaction between health conditions’ (diseases, disorders, injuries, traumas, etc.) and contextual factors [1][WHO ICF, 2001, p. 8]. This means that a distinction is made between an impairment and a disability. A disability occurs if a person´s impairment in interaction with surroundings means that one is limited in one’s actions and participation in social life.

This interaction can be viewed as a process or a result depending on the user.

‘Disability becomes known when impairments interact with their environments. So, disability is a social, relational, political and cultural entity that is lived through a very personal experience though shaped by some very public encounters.’ [Goodley, 2016]

This human perspective includes the opportunity to clarify differences between impairment and disability. An impairment does not in itself define a disability, only in the encounter with the environment will the relational circumstances define whether a disability occurs.

Our size, reach, strength, stamina, senses, cognition, etc. change throughout our lives; from childhood to old age. Some of us live with one or more impairment for a short period of our lives, others all our lives. Varying abilities are also combined with other markers of identity, such as gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, etc. which makes us even more complex, diverse, and unique as human beings.

Understanding disability as a social, relational, political, and cultural construct allows us to explore disability in relation to society. In this notion lies the opportunity to examine concepts such as culture, community, education, family structures, media, architecture, design, and so much more. It allows us to form an interdisciplinary understanding of what it means to be human, with or without impairment. Addressing these overall themes also allows us to explore who is left behind in progress towards a more equal and sustainable world.

On 25 September 2015, at the UN Sustainable Development Summit in New York, state and government leaders from around the world adopted the ambitious 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which aims to create a common vision and direction in the development towards a more equal, fair, and sustainable world.

By 2030, the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) must accelerate sustainable development for people and the planet on which we live. The SDGs are defined by 17 goals and 169 targets, which commit the UN’s 193 member states to end poverty and hunger in the world, reduce inequality, ensure good education, and better health for all, decent jobs, and more sustainable economic growth.

Illustration: Wandel and Ryhl

In the ambitious 2030 agenda, the overarching commitment to Leave No One Behind reads:

‘As we embark on this great collective journey, we pledge that no one will be left behind. Recognizing that the dignity of the human person is fundamental, we wish to see the Goals and targets met for all nations and peoples and for all segments of society. And we will endeavor to reach the furthest behind first.’

[2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development]

[UN’s Sustainable Development Goals]

Leave No One Behind is a commitment that emphasises that sustainability is about moving all of us in a direction, and in doing so, UN member states are committed to embrace the people who are left behind and to promote their active participation and potential for change. [https://www.verdensmaalene.dk]

UN member states recognise that development and growth, and the benefits they bring, do not automatically seep down through social and economic strata and contribute to the well-being of all. On the contrary, previous international goals have shown that development and growth can create an even greater gap between those who participate and those who are left behind.

In acknowledging the need to commit to Leave No One Behind, the UN also emphasizes the fact that sustainable development is only truly sustainable if everyone is included. All resources, competences, talents, and efforts must contribute and participate, if we are to fulfil the ambitious agenda of a sustainable future for our planet.

People are left behind when they cannot participate in and enjoy growth, development and progress. Similarly, those who live with disadvantages or deprivation that limit their life situation must be considered left behind. Those who are discriminated against based on one or more aspects of their identity, are also left behind, whether it be gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, social class, disability, religion, nationality, etc. [www.un.org/en/desa/leaving-no-one-behind]

In order not to leave people behind in sustainable development, the 193 member states of the UN have committed to work coherently with cross-sectoral knowledge and policymaking. The member states also have committed to identify the people who are left behind in their own country. The same applies to the circumstances that hinder people from participating in, and benefitting from development and progress on an equal footing with others. Specific needs of vulnerable people must be addressed so that they are met by policy frameworks which promote inclusive growth and prevent inequality. This means that, in the Danish context, we must identify and deal with those left behind in Danish society.

Research points to how people with disabilities are left behind in several different areas of ‘a lived life’ in Danish Society such as family life, education, employment, community participation and health. In the areas of education and employment in particular, there is a significant difference between people with and without disabilities.

Changing these Danish statistics and securing real inclusion and equality calls for multidisciplinary action and innovation. This will make sure that no one is left behind.

You will be able to acces the materials from the Bevica Scholarship Programme Ideation Workshops here – when it is available.

Universal design represents a basic view of humanity which recognises that diversity in functional ability and needs is a basic condition. It also means that when we have to accommodate great diversity – and sometimes opposing needs – in solutions, we can interpret universal design in two ways: Either the individual solution, which accommodates everyone whenever possible, and if this is not possible without resulting in the lowest common denominator, the universal solution can be a catalogue of solutions. For example, this could entail designing three ways to get into a building or across a road, and it is the catalogue of those three solutions that together make up the universal design solution. Because diversity in user needs requires diversity in solutions.

The selected cases show different ways of implementing this basic view of humanity in education, employment and leisure life.